The hidden world next door

How Icelanders learned to process grief through stories

We’ve been talking about trauma lately—specifically generational trauma and the hardships faced by the Icelanders in the days of old.

I confess that, even though I had a vague idea of what my ancestors had lived through, it was not until I went back to university in 2011 and started studying Icelandic history and folklore that my eyes were opened to what it was really like.

Similarly, I had an idea of my grandmother and great-grandmother’s stories, but had never placed them in the cultural context that gave them the power and gravity that they have.

It’s safe to say that the courses I took blew my mind wide open.

It was really by chance that I went back to uni at that time. I had never been able to finish a degree, even though I’d made an attempt on three separate occasions. As you may recall if you are aware of my story, I struggled quite a lot in the first four decades of life and was incapable of undertaking a programme of study.

Also, many of my experiences had put me off higher learning. Academic courses in the liberal arts (where my aptitude lay) seemed to me like a lot of pompous over-intellectualizing. I had grown up among people who valued intellectual prowess and excellence above all else, and devalued, even derided, the “softer” and more feminine aspects of life. From those folks I experienced a perpetual rejection of my humanity, so when I got to university, all that was activated tenfold and the internal conflict was unberable. I just couldn’t function.

That is, until I was nearly fifty. By that time I didn’t really care about getting a degree—for the most part, I had managed fine without one. But then Iceland had an economic meltdown, our leaders decided to apply to join the European Union, and interpreters from Icelandic into English were badly needed. I’d already done a bit of interpreting and really enjoyed it—so this really piqued my interest. I decided I wanted to apply … but the trouble was that I needed a degree.

After I got over my resentment about the unfairness of it all—a piece of paper did not make me any more qualified for a job I’d already been doing, in my opinion—I decided OKAY, if I needed a f*cking degree I’d get the degree, and since any old degree would do, I’d just take the easiest thing I could think of. Which for me was English.

So I started, and to my surprise I found that I enjoyed it. This experience of academia was very different from what I’d experienced previously. Here in Iceland, people of all ages were enrolled. Also, there was more openness to hearing different opinions and having discussion—it wasn’t just a single professor spouting rhetoric at the front of a lecture hall, then expecting everyone else to parrot back to him what he’d said in the next exam, like I’d experienced before.

The problem was, though, that the English department didn’t have a whole lot of variety in its courses. And so, I started looking at other options, and settled on doing a minor in Ethnology/Folkloristics, which had loads of super interesting classes.

And this is how I wound up learning about colonial Iceland, about life on the turf farms, about the oppression and survival of my people, and so much more. It turned out to be a fabulous experience, so impactful that I wound up writing several books on these subjects. By the time I was finished I had no interest in going to work in Brussels … but I had laid the foundations for a writing career!

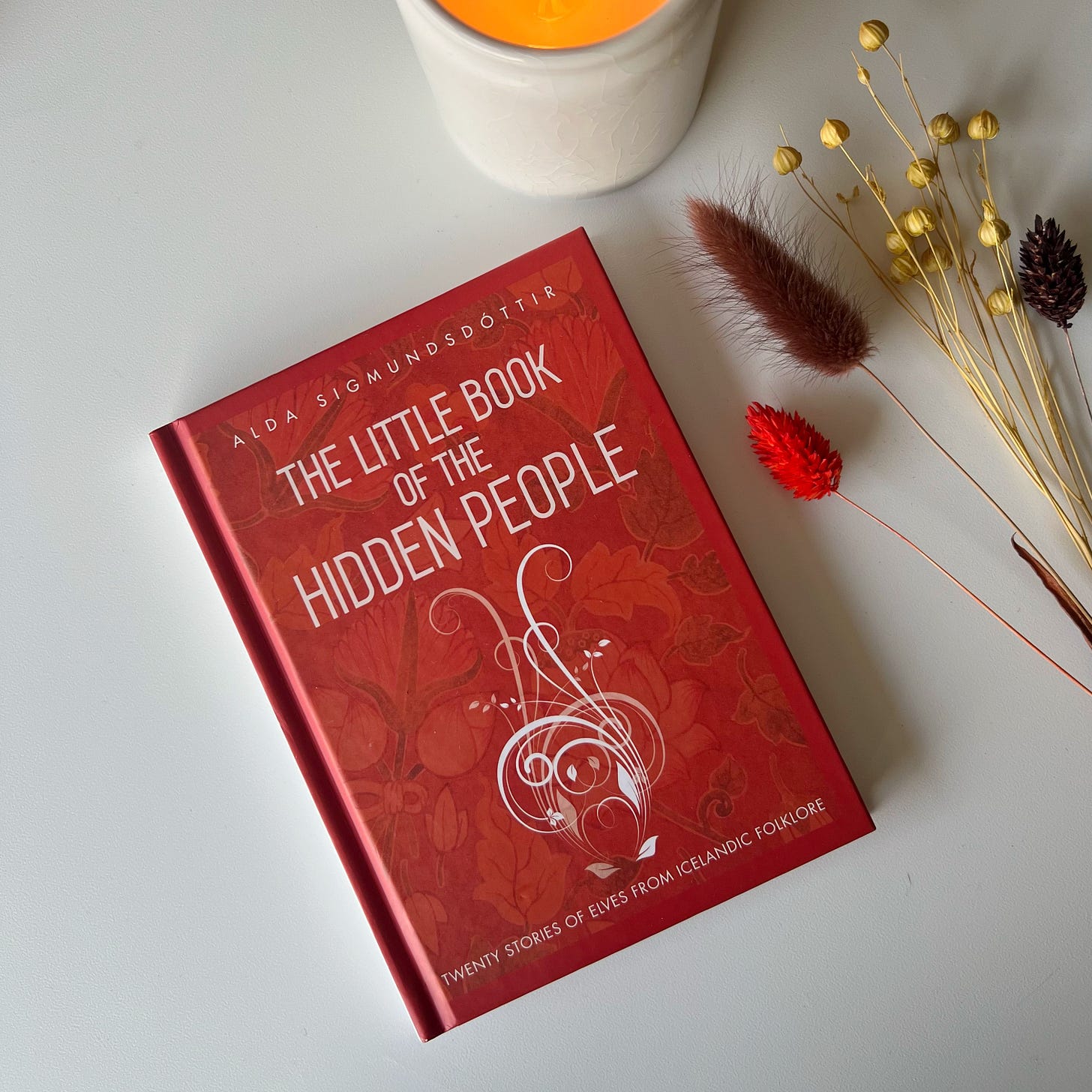

One of the most fascinating things I learned during my time of study is how the Icelanders used stories—in particular the stories of the Hidden People—to process their trauma and grief.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Letter from Iceland to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.