Things we carry and things we keep

How my great-grandmother's story reveals the legacy of systemic hardship in Iceland

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about Icelandic history and generational trauma—how the hardships of our ancestors are passed down to us, whether psychologically or genetically.

In the past year I had a couple of experiences that caused me to tap into a stratum in my subconscious that attaches to my maternal lineage—my mother, my maternal grandmother, and my maternal great-grandmother.

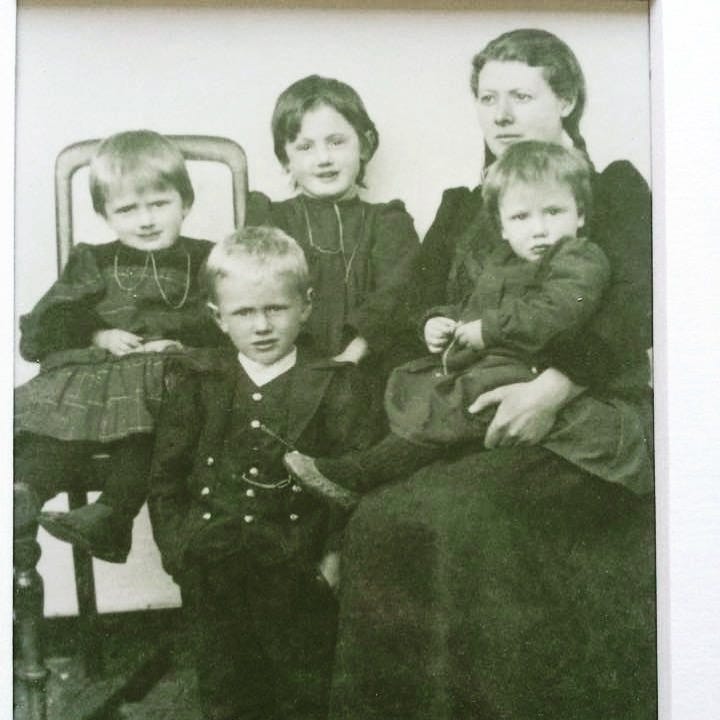

I have long been fascinated by the story of my great-grandmother, Þórdís Jónsdóttir, particularly after I learned the story behind this photograph of her with her four children—a photograph I recall seeing throughout my childhood, but which I never fully understood until later.

This photograph is taken shortly after Þórdís lost her husband, my great-grandfather, to the sea. He was 30 years old. The day after this photo was taken she knew she would have to send three of her children away from her, into foster care.

She was allowed to keep one child with her, and she chose Guðrún, the oldest, who at the time was five. My grandmother, Elínborg, is the one sitting on the chair. She was two. Her brother, Stefán, was three, and her younger sister, Signý, was one.

I am haunted by the grief in Þórdís’s face. To be forced to give away your children and be sent to be a labourer on a farm, doomed to a life of poverty with no chance of ever having your children returned to you.

I cannot even imagine.

Yet my great-grandmother’s story is the story many Icelandic families—so, so many. This was a time when systemic oppression was built into the system of government, when households were routinely dissolved if and when the breadwinner died (which was often) even if the widow (it was usually a widow, very occasionally a widower) was capable of continuing the running of the farm.

This dissolution meant that children were auctioned off to the lowest bidder (since the district paid a stipend with each child, they were given to whoever was willing to take them for the lowest amount), and the surviving parent was forced into virtual slavery.

The ostensible reason behind this was to prevent people from living in abject poverty, but the probable reason was that it ensured cheap or free labour for wealthy farmers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Letter from Iceland to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.