When my great-grandmother Þórdís Jónsdóttir lost her husband to the sea, her fate was that of so many other Icelandic families who suffered the same: the district stepped in, dissolved the family, auctioned off Þórdís’s belongings, and sent the children into foster care.

[Continued from last week’s post:]

Things we carry and things we keep

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about Icelandic history and generational trauma—how the hardships of our ancestors are passed down to us, whether psychologically or genetically.

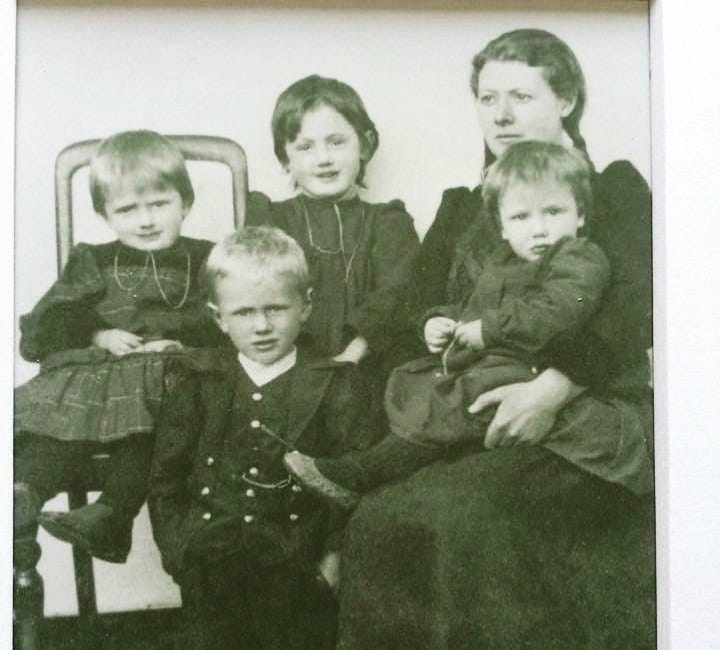

(Aside: it strikes me how, despite poverty and hardship, the children were so well dressed and cared for, as evidenced by the above photo. It puts me in mind of slums I saw in India, where the women wore beautiful saris made of the most gorgeous silk, all while living in ramshackle huts with no sanitation. It just goes to show how human dignity cannot be subordinated by systemic oppression.)

She was, however, allowed to take one of her children with her. She had to choose between them, and chose the oldest, Guðrún, who was five.

I have wondered why she made that choice. Why she didn’t choose the youngest, Signý, who was only a year old and arguably needed her mother the most.

The answer, most likely, is that she chose Guðrún because Guðrún was able to work.

Such was the harsh reality of life in the early 1900s—and, indeed, in the centuries preceding. Children as young as five were made to work, very often watching over the sheep in remote mountain pastures, making sure they didn’t stray, or weren’t attacked and killed by foxes.

Meanwhile, Þórdís’s other three children—Stefán, Elínborg (my grandmother) and Signý—were sent to live at other farms in the district.

When children were fostered out, the district paid an allowance with each child to help with their upkeep. This took the form of an auction of sorts, where farmers bid to take a child, and the farm with the lowest bid—willing to take the child for the least amount of money—usually got the child. Concern for the child’s welfare was rarely the highest priority, and there are many stories of harsh and cruel treatment of foster children who were subject to abuse and starvation, and made to perform tasks way beyond their level of maturity.

The allowance that the district paid with the children accumulated as a debt that the surviving parent was required to repay. Until they did, some of their rights were revoked, including the right to remarry. Repayment of a debt was not likely to happen when a mother, say, was forced to become a farm labourer with no salary, as was common. Where would she get the money?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Letter from Iceland to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.